Responsible researcher: Eduarda Miller de Figueiredo

Article title: PARENTING WITH STYLE: ALTRUISM AND PATERNALISM INTERGENERATIONAL PREFERENCE TRANSMISSION

Article authors: Matthias Doepke and Fabrizio Zilibotti

Location of intervention: OECD countries

Sample size: 66,632 observations

Sector: Education

Type of intervention: Effects of parenting style

Variables of interest: Relative Risk Rates associated with inequality

Evaluation method: Experimental Evaluation (RCT)

Policy Problem

What drives the way parents raise their children? Can parenting be shaped by economic incentives and constraints? In this article, the authors construct a theory of rational choice that is responsible for variations in child-rearing across industrialized countries, in which the model considers that parents are driven by a combination of Beckerian altruism and paternalistic motives.

Beckerian altruism refers to a concern for the well-being of the child and paternalism captures the extent to which parents can affect their children's choices by shaping their preferences or imposing restrictions on their choices. Thus, the constructed theory conjectures that disagreements about choices have an influence on investment in human capital and economic success is a key factor in choosing a parenting style.

According to Weinberg (2001), parents influence their children's behavior through financial incentives, in which low-income parents, as they do not have access to financial incentives, resort to authoritarian methods. Lizzeri and Siniscalchi (2008) state that parents who have superior information about the consequences of certain actions can interact to protect children from ill-informed choices.

Assessment Context

Parenting styles vary across countries with different income inequalities, returns to education, redistributive policies and quality of institutions. Thus, the focus of the study is the analysis of the correlation between inequality and the choice of parenting style. In more unequal societies, success and failure are associated with greater income gaps, so it is expected that parents will be able to interfere more in the nature of their children.

The anti-authoritarian period is linked to a low return to education, that is, in the 1960s-1970s economic inequality reached a historic low and there was little unemployment, so the return on forcing children to study was very low, giving greater freedom and independence to the children.

Therefore, the choice of parenting style depends on the interaction between parental preferences and characteristics of the socioeconomic environment. The constructed theory is consistent with historical trends in parenting styles in industrialized countries, thus authoritarian parenting, measured by practices such as corporal punishment, has decreased over time.

Policy Details

Through the classification of “parenting styles”, the authors define the following styles (Baumrind, 1967):

In the constructed model, authoritative parenting can create a form of guilt that induces the child to avoid choices that the parents consider inappropriate.

The research used a sample of all OECD countries [1] , this choice was made because they are all similar in terms of general level of development and other aspects of culture and institution, factors that can affect parents' choices. Parenting style measures are assembled using the World Value Survey (WVS) where questions are asked along the lines of: “ Here is a list of qualities that children can be encouraged to learn at home. Which, if any, do you consider especially important? Choose up to five. ”

Methodology Details

From the research, proxies of the three parental practices were created considering the quality most associated with the parenting style. The value most associated with authoritarians is obedience, therefore all parents who marked obedience as a desired quality were labeled as “authoritarian”. For “authoritative” parents, those (i) non-authoritarian and (ii) who mention hard work among the qualities listed were selected. Finally, “permissive” parents are those who (i) are neither authoritarian nor authoritative and (ii) list independence or imagination as an important quality.

The three categories are mutually exclusive but not exhaustive, meaning some parents may not be associated with any category. Considering the total sample of 66,632 respondents, 27% are authoritarian, 30% are authoritative, 34% are permissive and 9% of the sample was excluded as they were not classified in any category.

To carry out the study analysis, the authors analyzed the relative risk rates (RRRs) associated with inequality through multinomial logistic regressions with country fixed effects. Additionally, the authors controlled for age, age squared, religiosity, education (less than high school, high school, and higher education), and the country's GDP per capita.

Another analysis carried out was considering after-tax income, given that if expectations regarding children's economic outcomes and exposure to risk drive the choice of parenting style, then the extent of taxation should also matter. Thus, we considered (i) a measure of redistributive tax progressivity from the Andrew Young School of Policy Studies (2010) and (ii) a measure of social spending as a percentage of GDP.

Results

When analyzing the data in a first step, the authors realized that the permissive parenting style is negatively correlated with inequality, while authoritative and authoritarian are positively correlated. For example, inequality is very low in Sweden and Norway and these countries have higher percentages of permissive parents, while the United States has higher inequality and parents are more authoritarian and more authoritarian.

The effect found for religiosity demonstrated that religious parents are less permissive and more authoritarian than non-religious people. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that parents prepare their children for the world in which they expect them to live, that is, religious believe that the world is regulated by an order that never changes and, therefore, they must transmit to their children a set of immutable values and truths. When considering the extent of taxation, the findings suggest that an increase in social expenditure or progressive taxation is associated with a significant drop in the likelihood of authoritative and authoritarian parenting relative to the permissive style. That is, more redistribution makes those more permissive.

Educational outcomes also demonstrated that characteristics of the educational system affect parenting style. In some countries, vertical teaching and memorization of facts are emphasized in high school, in addition to access to the best universities through high-stakes exams. In such countries, parents have a stronger incentive to demand greater effort from their children during adolescence, which may take the form of an authoritative or authoritarian style. In countries with good institutions and strong civil rights protections, parents can expect that children's natural inclinations will help them achieve success.

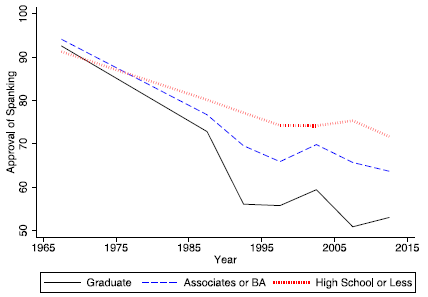

Figure 1: Parental Education and Approval of Corporal Punishment

It has also been observed that increases in parental education are associated with a decreased propensity to be authoritarian and an increase in the propensity to be authoritative. Figure 1 even demonstrates that there is greater parental involvement in education and less education in approving corporal punishment when parents are more educated, while parents with less education are more likely to resort to authoritarian methods.

Public Policy Lessons

The difference in the parenting style that parents impose on their children may be an effect of the economic environment, thus, the theory created can suggest that the authoritarian style decreases as economic development advances. There is evidence that in countries with lower inequality, parents are more permissive and emphasize values such as independence and imagination, while in countries with high inequality, parents point to a more authoritarian style in upbringing.

Reference

DOEPKE, Matthias; ZILIBOTTI, Fabrizio. Parenting with style: Altruism and paternalism in intergenerational preference transmission. Econometrica, vol. 85, no. 5, p. 1331-1371, 2017.

[1] The sample includes: Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the United States.