Responsible researcher: Eduarda Miller de Figueiredo

Authors: Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, James A. Robinson

Location of Intervention: Group of countries

Sample Size: -

Sector: Economic Development

Variable of Main Interest: Effect of institutions on per capita income

Type of Intervention: Mortality Rates and Risk of Expropriation

Methodology: 2SLS

Summary

To fill the gap in estimates of the effect of institutions on economic performance, the impact of these institutions on performance was estimated using a source of exogenous variation, based on a theory based on three installations. The hypothesis of the study is that the mortality of settlers affected the settlements, in which the settlements affected the first institutions and, as a result, the first institutions persisted and formed the basis of current institutions. Through a 2SLS, it was demonstrated a strong correlation between institutions and economic performance and that the mortality rates of settlers 100 years ago explain more than 25% of the variations in current institutions.

Differences in institutions and property rights have received considerable attention when trying to answer what are the fundamental causes of the large differences in per capita income between countries. In which countries with better institutions, more secure property rights and fewer distortions in international policies, will invest more in physical and human capital, which makes it possible to use these factors more efficiently to achieve a higher level of income (North, 1981; Knack and Keefer, 1995; Rodrik, 1999).

At some level, it is obvious that institutions are important. However, there was - at the time of the study discussed here - a gap in reliable estimates of the effect of institutions on economic performance. Because of this, the authors estimated the impact of institutions on economic performance using a source of exogenous variation in institutions, in which a theory of institutional differences between countries colonized by Europeans was proposed [1] . Thus, exploring this theory to derive a possible source of exogenous variation.

The theory proposed by the authors is based on three installations:

The authors' hypothesis is that settler mortality affected settlements, in that settlements affected early institutions, and as a result, early institutions persisted and formed the basis of current institutions.

Based on the premises listed in the theory proposed by the authors, mortality rates expected by the first European settlers in the colonies were used as an instrument for current institutions in these countries. Europeans were well informed about these mortality rates at the time, although they did not know how to control the diseases that caused these high mortality rates.

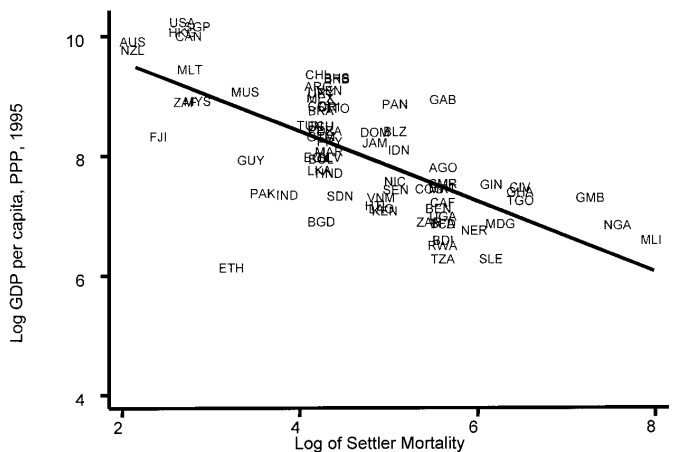

Figure 1: Relationship between colonizer income and mortality

Figure 1 plots the logarithm of GDP per capita in the year of the study (2001) against the logarithm of colonizer death rates per thousand for a sample of 75 countries. A strong negative relationship is presented, in that colonies where Europeans faced higher mortality rates are currently poorer. For the authors, this reflects the effect of the mortality of colonists working in institutions brought by Europeans.

With these considerations, together with data on the mortality of the local population and population density before the arrival of Europeans, leads the authors to believe that the mortality of settlers is a plausible instrument for institutional development: the diseases of the time affected settlement patterns. Europeans and the type of institutions they established, but it had little effect on the health and economy of indigenous peoples.

The authors regressed the current performance of institutions and instrumentalization on settler mortality rates. Political Risk Services “dispossession risk” protection index was used as a proxy for institutions. In which this variable measures differences in institutions originating from different types of states and state policies. Political Risk Services reports a value between 0 and 10 for each country and year, with 0 corresponding to the least protection against expropriation. The authors used the average value for each country between 1985 and 1995.

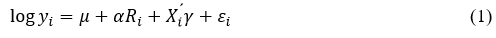

A linear regression was regressed, using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) method, according to this equation:

where yi is the per capita income in country i

, Ri

is the protection against “expropriation risk”, Xi

is a vector of covariates, and ei is a random error term. The coefficient of interest throughout the article is the effect of institutions on per capita income.

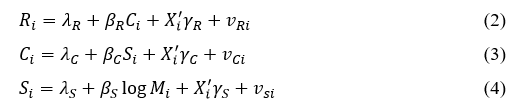

In addition to this equation that describes the relationship between current institutions and the logarithm of GDP, the following equations are presented:

where R is the measure of current institutions (protection against expropriation between 1985 and 1995), C

is the measure of beginning institutions, and M

is the mortality faced by settlers. In which, the simplest identification strategy is to use Si

or Ci

as an instrument for Ri

. However, to the extent that settlers are more likely to migrate to wealthier areas and early institutions reflect other characteristics that are important for current income, the identification strategy would be invalid (i.e.,

Ci and Si could be correlated with ei

). Therefore, the mortality rates faced by the colonists, the logMi

, was used as an instrument to evaluate

.

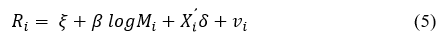

Therefore, the two-stage least squares estimates of equation (1), the protection against expropriation variable (Ri ), is treated as endogenous and modeled as:

where is the death rate of colonists at average strength of 1,000.

The results show that the mortality rates faced by colonists more than 100 years ago explain more than 25% of the variation in current institutions.

Furthermore, the findings suggest a strong correlation between institutions and economic performance. And this relationship should not be interpreted as causal, since rich economies may be able to afford (or perhaps prefer) better institutions. Furthermore, they point out that there are many omitted determinants of income differences that are naturally correlated with institutions and, finally, they describe that measures of institutions are constructed ex-post, and analysts may have had a natural bias to see better institutions in richer places.

It was also demonstrated that this relationship occurs through hypothetical channels: the (potential) mortality rates of settlers were one of the main determinants of settlements, which were one of the main determinants of the first institutions [2] ; and there is a strong correlation between early institutions and current institutions.

The study emphasizes the colonial experience as one of the many factors that affect institutions. Since the mortality rates faced by colonists are arguably exogenous, they are useful as a tool for isolating the effect of institutions on economic performance.

For the authors, these results suggest substantial economic gains from improving institutions [3] . Furthermore, the results indicate that reducing the risk of expropriation results in significant gains in per capita income, but do not indicate that concrete measures lead to an improvement in these institutions.

Reference

ACEMOGLU, Daron; JOHNSON, Simon; ROBINSON, James A. The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. American economic review , vol. 91, no. 5, p. 1369-1401, 2001.

[1] The authors here refer to the “colonial experience” as European influence on the rest of the world.

[2] In practice, institutions in 1900.

[3] For example, as in the case of Japan during the Meiji Restoration or South Korea during the 1960s.