Responsible researcher: Eduarda Miller de Figueiredo

Authors: Jason Abaluck and Jonathan Gruber

Intervention Location: United States

Sample Size: 477,393 individuals

Sector: Healthcare

Variable of Main Interest:

Type of Intervention: Health Plan

Methodology: Logit

Summary

Medicare is a program that provides universal health insurance coverage for people over age 65 and those in the disability insurance program . In 2003, through a law modernizing this program, benefits for prescription drugs were added – Part D. The article sought to investigate the choice of elderly people based on the plans available after modernization. Using the conditional logit model and discrete choice models, the authors realized that individual choices are consistent with maximizing behavior.

Medicare Modernization Act [1] , which occurred in 2003, represented a more significant expansion of the United States' public insurance programs by adding the Part D Medicare program . For this expansion, several private insurance companies were used to provide this new product for public insurance.

Medicare is a program that provides universal health insurance coverage for people over age 65 and those in the disability insurance program . The program, until expansion, covered most medical needs but excluded coverage for prescription drugs. Medicare beneficiaries spent an average of $2,500 each on prescription drugs in 2003, which is more than double what the average American spent on all health care in 1965 (the year Medicare ).

The article seeks to investigate the choices of elderly people for the newly created Part D in 2006.

In 2003, the US government and Congress agreed to a package of prescription drug benefits at a projected cost to the federal government of $40 billion per year over the first ten years. The innovation of Part D is due to the fact that it is provided by private insurers under contract with the government.

According to Duggan, Healy, and Morton (2008), standard economic theory would suggest that the beneficial feature of the plan is precisely that it allows individuals to choose from a wide variety of plans that meet their needs, rather than restricting them. to a limited set of choices made by the government. However, Iyengar and Kamenica (2006) point out that not only the decision to participate in a market, but also the nature of the choice itself is affected by the size of the set of options.

Heiss, McFadden and Winter (2006), when studying Part D , assessed whether intentions to enroll in the plan were “rational”, which led to the discovery that for the majority of potential enrollees, the decision to enroll or not appears to be made rationally.

Beneficiaries could choose between three types of private insurance plans that cover their medication expenses, namely:

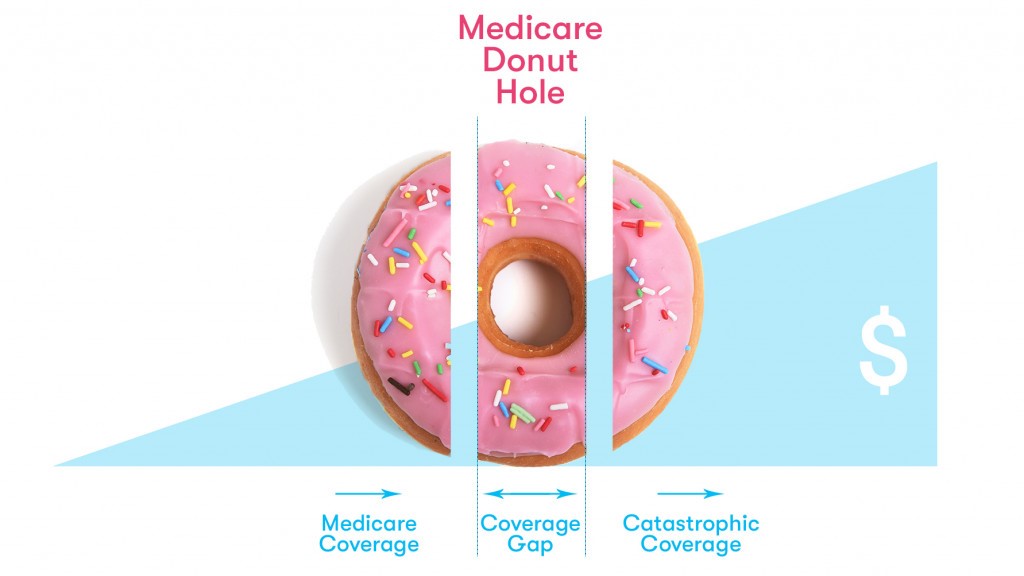

Under Part D , beneficiaries are entitled to basic prescription drug coverage according to the following structure:

Enrollment in Part D plans was voluntary for eligible Medicare , but low-income seniors who received prescription drug coverage through state Medicaid were automatically enrolled—the “dual eligible.” Plans for the “dually eligible” could charge co-payments of just $1 for generics and $3 for brand-name drugs that were below the poverty line, and $2 for generics and $5 for brand-name drugs that were above the poverty line. poverty line.

There was enormous interest from insurers in participating in the program, more than 3 thousand plans were being offered to potential Part D . In June 2006, there were 10.4 million people enrolled in the PDP plan, 5.5 million in the MA plan and around 6 million “dually eligible”.

The authors used a sample prescription drug record from Wolters Kluwer (WK) Company for 1.53 million seniors who:

Part D plans was also used from four files provided by CMS: plan information, beneficiary cost, formulary, and geographic location.

When cleaning the entire sample, focusing only on PDP plans and excluding individuals who have fewer than 500 observations in their state, the final sample consists of 477,393 individuals.

To analyze the plan using the conditional logit model, the authors use several discrete choice models, as they allow controlling the additional characteristics of the plan, allow us to understand more precisely how preferences combine with the characteristics of the set of choices and allow the well-being consequences of choices to be quantified.

Model 1, which includes only the premium, realized direct costs, variation in direct costs, and quality variables, shows that a $100 increase in premiums leads to a 32% reduction in the probability of a given plan being chosen. . In Model 2, which adds additional covariates to control for deductibles, donut hole coverage, average cost sharing, formulary coverage, and plan quality, the coefficient on premiums increased, suggesting that it was initially biased downward due to to the omitted variable bias. That is, the coefficient on the variance term drops even further when a control for the number of the 100 most popular drugs included on the plan's formulary was added.

According to the authors, for the result of model 2, one explanation is that although individuals prefer plans that cover more medications, they do not have enough foresight to choose plans that cover medications that they may need in the future but are not yet taking. .

In models 3 and 4, binary variables of brand and brand status were added. The premium coefficient decreased when the authors included fictitious brands, but the premium effects remain large: a $100 increase in annual premiums leads to a 50% reduction in the probability of a plan being chosen. The coefficients on plan characteristics are very large in all specifications. Model 4, which has the lowest plan features, suggests that individuals are willing to pay more than $300 for full “donut hole” coverage, $50 for generic “donut hole” coverage, and $12 for each one of the top 100 medications appearing on the formulary.

In the end, the authors conclude that the distribution of health plan coverage would be quite different if there were no inconsistencies in choices. It was estimated that the share with some “donut hole” coverage would fall by 40% if these inconsistencies were corrected.

Although individual choices are consistent with maximizing behavior, such as preferring lower out-of-pocket spending and higher quality, they are inconsistent with the standard model in three respects: individuals underestimate out-of-pocket spending relative to premiums, they overestimate plan features , and do not fully appreciate the risk reduction aspects of plans for themselves.

References

Duggan, M.; Healy, P.; Morton, F. S. (2008). Providing prescription drug coverage to the elderly: America's experiment with Medicare Part D. Journal of Economic perspectives , 22 (4), 69-92.

Heiss, F.; McFadden, D.; Winter, J. (2009). Regulation of private health insurance markets: lessons from enrollment, plan type choice, and adverse selection in Medicare Part D (No. w15392). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Iyengar, SS; Kamenica, E. (2006). Choice overload and simplicity seeking. University of Chicago Graduate School of Business Working Paper , 87 , 1-27.

[1] Medicare Modernization Act of 2003.