Responsible researcher: Eduarda Miller de Figueiredo

Article title: RURAL ROADS AND LOCAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Article authors: Sam Asher and Paul Novosad

Location of intervention: India

Sample size: 11,432 villages

Sector: Job Market

Type of intervention: Effects of road construction

Variables of interest: variable created by subtracting the treatment limit from the village population

Evaluation method: Discontinuous Regression - fuzzy

Policy problem

Worldwide, there are almost a billion people living in places more than 2 kilometers away from a paved location, with a third of these people in India (World Bank Group, 2016). Seeking a solution to this problem, the government of India launched a roads program to finance road construction, the Prime Minister's Village Road Program (PMGSY).[1].

The literature states that road construction is associated with increases in growth, both agricultural and non-agricultural, as well as reducing poverty. Whereas, paved roads would reduce input prices with higher output prices, increasing the production of non-agricultural goods, which would be offset by higher wages. The variation in prices between these markets is the main argument that rural roads would help develop the rural economy, internally and externally.

However, if the villages have few exports, they may cause little demand for transport that operators would not be willing to pay the fixed cost to reach the village, thus, the problem of high transport costs after the construction of paved roads would continue.

Assessment context

The PMGSY is based on the idea that poor roads are the biggest obstacle to rapid rural development (National Rural Roads Development Agency, 2005) and, by 2015, had benefited the construction of roads connecting almost 200,000 villages, at a cost of almost 40 billion of dollars.

The implementation of the program was in places that had population limits: villages with more than 1,000 inhabitants in 2003, with more than 500 people in 2007 and with a population of more than 250 after 2007, according to data from the 2001 population census. By 2015, more More than 400,000 kilometers were built at a cost of almost 40 billion dollars.

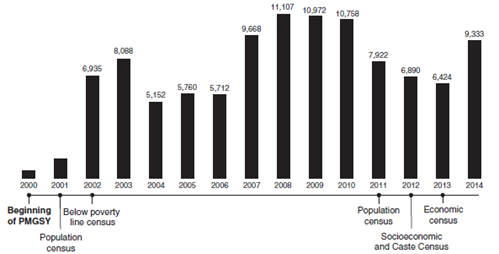

Figure 1: Road construction data through PMGSY by year

Figure 1 presents data on road construction per year, where it is possible to see that construction was insignificant until 2001, increasing in the following years until reaching a peak of 11,107 villages receiving roads in 2008 and, after, reducing the number of roads again. roads.

Policy Details

To carry out the research, two population limits were used in the villages: 500 and 1,000. Villages that exceed these limits were 22 percentage points more likely to receive a paved road. Thus, the authors overcame the obstacle of the correlation between road construction and the economic and political characteristics of the locality, allowing the causal impact to be estimated through of the regression discontinuity method (rd).

A complete database was built that has information on all companies and families in rural areas of India, with geographic and socioeconomic data on individuals, identities and characteristics of villages, and characteristics of firms [1] . With the data, a consumption proxy

The impacts of investment in infrastructure are complex to analyze as they have a high cost and a large potential for return, so the allocation is not random on the part of policymakers. Thus, there are not a sufficient number of treaties and controls, but the authors managed to overcome this obstacle by combining almost random variations of the program rules with georeferenced village-level data.

As the population limit rules do not change discontinuously, the probability of treatment will increase discontinuously in these limits, making it possible to estimate the effect of new roads through a fuzzy , in which the dependent variable will be the subtraction of the treatment limit from the village population . fuzzy rd estimator calculated the local average treatment effect (late) of receiving a new road for a village with a population equal to the threshold (+500, +1,000).

As control variables we used the indicators of the presence of a primary school, medical center and electrification in the village, the log of the total area of agricultural land, the portion of agricultural land that is irrigated, the distance from the nearest density city, the proportion of workers in agriculture, the literacy rate, the share of inhabitants belonging to the scheduled caste, the share of families with their own agricultural land, the share of families that are subsistence farmers and the share of families that earn more than US$4 per year. month [2] .

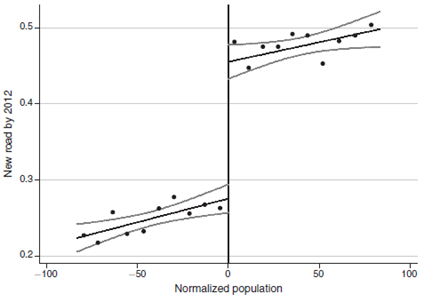

Figure 2: Effect of probability of new roads in 2012

Figure 2 shows the proportion of villages that received new roads before 2012 in each population group. A discontinuous increase in the probability of treatment is observed at the threshold where, crossing this threshold, the probability of treatment increases by 21-22%.

Results

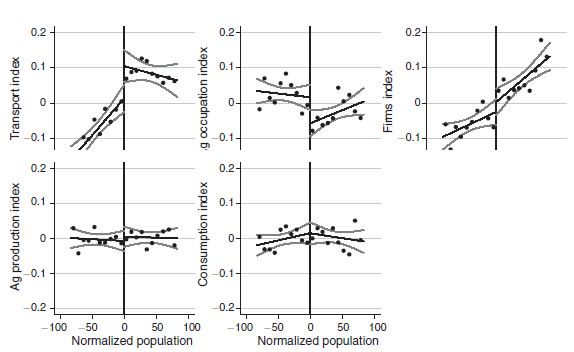

The results show a large positive effect on transportation service availability, a significant reallocation of labor away from agriculture, and a smaller positive effect on employment growth in small businesses. Such results can be observed in Figure 5, which presents graphic representations for each variable, demonstrating that significant effects appear in transportation and labor output, but little impact on companies.

Figure 3: Effect of roads on indices of main results

A new road causes a significant increase of 12.9 percentage points in the availability of public bus services. More expensive means of transport, such as taxis and vans, did not see significant growth, but cheaper private motorized transport ( autorickshaws ) showed growth. Therefore, it was possible to observe that the new roads significantly affect connections with the external market.

The results for occupational choice suggested that new roads cause a 9.2 percentage point reduction in agricultural workers and a 7.2 percentage point increase in non-agricultural workers. As land is the main input for agricultural production, when analyzing the results for this index, it was noticed that a new road does not significantly change the proportion of families that do not have land.

Regarding the characteristics of individuals, the results suggest that men are more likely to leave agriculture, as are younger people. This result could be an exemplification of the physical advantage of men in non-agricultural work or an attitude against female work away from home, as stated by Goldin (1995), however the estimates of the average control group for male and female workers are very close. .

It was also estimated a 27% increase in employment in non-agricultural firms and a significant 33% growth in retail in response to a new road, which creates an average of 4.2 new jobs in the village when the road is built. Thus, the authors believe that this is evidence that suggests that roads facilitate access to the external labor market more than the growth of jobs in village companies.

The authors found no evidence of increases in ownership of mechanized farms or irrigation equipment, nor did they observe any effect on earnings, assets or consumption. In short, according to the authors, the results demonstrate that there is no effect on the structure of agricultural production with the new roads.

Public Policy Lessons

The construction of new roads has substantial impacts on economic activity, facilitating the reallocation of agricultural labor, however it does not generate major economic changes. In other words, rural roads increase transport services and reallocate labor outside of agriculture, but do not bring about major changes in village businesses.

Reference

ASHER, Sam; NOVOSAD, Paul. Rural roads and local economic development. American Economic Review, vol. 110, no. 3, p. 797-823, 2020.

[1] Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana.

[2] Name of the databases used: Socioeconomic High-resolution Rural-Urban Geographic Dataset (SHRUG), PMGSY, Socioeconomic and Caste Census (SECC) and Below Poverty Line (BPL).

[3] Approximately 250 INR (Indian rupees).