Responsible researcher: Eduarda Miller de Figueiredo

Original Title: Social Security and Retirement: An International Comparison

Authors: Jonathan Gruber and David Wise

Intervention Location: France, Belgium, Netherlands, Italy, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom, Switzerland, United States and Japan

Sample Size: 11 countries

Sector: Social Security

Variable of Main Interest: Unused work capacity

Type of Intervention: Retirement

Methodology: Others

Summary

The decline in labor force participation of older people is perhaps the most dramatic feature of labor force change over the decades. This variation has resulted in enormous pressure on the viability of the social security system in countries. This article analyzed the evidence from 11 articles from industrialized countries that have been affected by this situation. The findings suggest a strong relationship between social security incentives to quit work and older workers leaving the workforce.

The population is aging rapidly in all industrialized countries and this puts enormous pressure on the viability of the social security system in these countries. This is also accompanied by a trend that workers are leaving the workforce earlier and earlier. According to the authors, one of the explanations for this event is that social security provisions are a huge incentive to leave the workforce early, because of its structure that ends up aggravating the financial problems faced by the population.

For this reason, in the article discussed here, the authors seek to draw attention to the important role that social security plays in work decisions for older people. To this end, a comparison of evidence described in 11 articles from industrialized countries was presented.

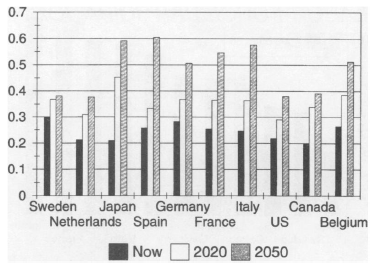

In Figure 1, the authors present the difference in the proportion of the number of people aged 65+ in relation to the number of people aged between 20 and 64 years for the study period (2014) and in future years, for the countries analyzed.

Figure 1: Proportion of the population aged +65 in relation to the population aged between 20 and 64.

Source: Gruber and Wise (2014).

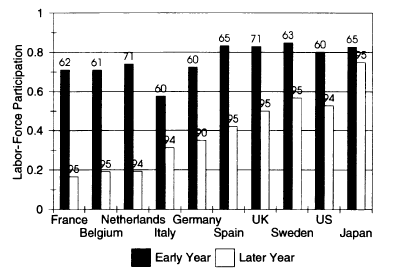

In the early 1960s, labor market participation rates were above 70% in practically all countries. However, in the mid-1990s, the rate fell to less than 20% in Belgium, Italy, France and the Netherlands, as can be seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Decline in labor force participation, age 60-64[1]

Source: Gruber and Wise (2014)

By the age of 50, approximately 90% of men are in the workforce in all countries. However, after the age of 50, there is a very large variation between countries. For example, in Belgium, at age 65 less than 5% of men are working. In Japan, almost 75% of men remain in the workforce at age 60 and, at age 65, 60% continue to work.

There are two features of social security plans that have an important effect on incentives for labor force participation:

Assuming that a person acquired, at age x , the right to future benefits after retirement. The current discounted value of these benefits, minus taxes, is the person's social security assets at that age (SSWa) [2] . Therefore, the main consideration in making retirement decisions is how this SSWa wealth will evolve in the event of continued work. The difference between the SSW if retirement is at age x and the SSW if retirement is at age x+1 [3] , is called current SSW. The authors compared SSW accumulation with net wage earnings throughout the year. If the accumulation is positive, it adds to the total remuneration for the additional year's work, but if negative, it reduces the total remuneration. In which a negative increase discourages continuation in the workforce and, in the case of a positive increase, the logic is reversed.

There are many implications with the departure of older men from the workforce, such as the abdication of these men's productive capacity.

The authors consider the proportion of men not working at a given age (1-LFP), where LFP is the labor force participation rate [4] . In Belgium the proportion is 0.95 and in Japan 0.40 at age 65.

The authors refer to this measure as “unused productive capacity” at this age. If the unused capacity is summed over all ages in some interval, the area above the LFP curve in that interval is found. Dividing by the total area above and below the curve for that age range, then multiplying by 100, provides an approximate measure of unused capacity within an age range, as a percentage of the total working capacity in that age range.

To illustrate what is discussed, the authors use data from France, where labor force exit rates correspond with social security provisions.

The so-called “tax force for retirement” was also studied for all countries. To do this, the authors added the implicit tax rates on work from age 55 to age 69. That is, a measure based on earnings from ongoing work as a person approaches eligibility for social security benefits.

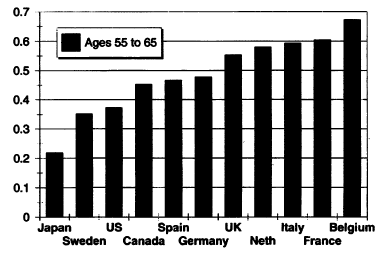

In Figure 3, measures of unused productive capacity are presented for all countries studied for the age group between 55 and 65 years old. Belgium had 67% of unused production capacity, while Japan had only 22%.

Figure 3: Unused Production Capacity (Proportion)

Source: Gruber and Wise (2014)

According to the authors, pension accumulation (SSW) is typically negative at older ages, that is, continued employment implies a reduction in the discounted present value of pension benefits.

The collective evidence for all countries combined shows that the age of social security eligibility contributes significantly to early labor force exit. Additionally, unemployment and disability programs serve as early retirement programs in many countries.

Results from France show that social security benefits are first available at age 60. And the age-specific labor force exit rate jumps to approximately 60% in this age group.

The high dropout rate at early retirement age in France also illustrates the role of the implicit tax rate on work imposed by social security plan provisions. In early retirement, the implicit tax rate is almost 70% for people with average lifetime earnings.

By observing this relationship for all countries studied, the authors found that the relationship between the implicit social security tax on work is strongly related to the labor force participation of older people.

The results for calculating the “tax force to retire” find a clear relationship: there is a strong correspondence between the tax force to retire and the unused work capacity. However, the relationship is non-linear, in that the regression of unused labor capacity against the logarithm of fiscal strength indicates that 82% of the variation in unused capacity can be explained by the pensionable labor force to retire. Therefore, the data suggest a strong relationship between social security incentives to quit work and older workers leaving the workforce.

The conclusion suggests that the provisions of the social security program actually contributed to the decline in the participation of older people in the labor force, reducing the potential productive capacity of the labor force.

[1] The numbers above the histogram bars show the corresponding year of data used for each country.

[2] SSWa = Social Security Wealth at that Age .

[3] In mathematical terms: .

[4] LFP = Labor-Force Participation Rate .