Responsible researcher: Eduarda Miller de Figueiredo

Author: James J. Heckman

Location of Intervention: -

Sample Size: -

Sector: Education

Variable of Main Interest: Cognitive and non-cognitive skills

Type of Intervention: Family environment

Methodology:-

Summary

In this article, a general synthesis was made of several studies that analyze human development and the relationship with environments and experiences in early life. Heckman presented several references that highlight this relationship, in addition to an analysis of the return rate of interventions carried out and an analysis of second chance programs. Finally, it was concluded that there is a great impact of the child's early environment on their cognitive development. In addition to reinforcing that early interventions aimed at disadvantaged children have much higher returns than later interventions

The literature concludes that virtually every aspect of early human development, from the brain's evolving circuitry to a child's capacity for empathy, is affected by the environments and experiences the child has been exposed to between the prenatal and postnatal period. from the earliest years of childhood. Since early family environments are the main predictors of cognitive and non-cognitive skills (Carneiro and Heckman, 2003; Cunha et al., 2006).

According to the author, this occurs because of two characteristics that are intrinsic to the nature of learning: (i) early learning gives a “value” to acquired skills, consequently leading to a “self-incentive” to learn more; (ii) early mastery of cognitive, social and emotional skills makes learning at later ages more efficient (Shonkof and Phillips, 2000).

Many of the main economic and social problems can be attributed to the low levels of qualifications and skills of the population. In the United States there will be many fewer graduates included in its workforce in the next 20 years than in recent years, where it is also important to highlight that more than 20% of the American workforce is functionally illiterate (Delong, Katz and Goldi, 2003 ; Ellwood, 2001; Statistics Canada, 2002).

Research has demonstrated the early emergence and persistence of gaps in cognitive and non-cognitive skills. In environments that do not stimulate and encourage these skills from an early age, they place children at an early disadvantage. According to the Colema Report , it is families, not schools, that are the main sources of inequality in student performance (Coleman, 1966).

Therefore, being a source of concern as family environments deteriorate. More and more American children are being born to teenage mothers or living with “solo parents”, in which such situations are associated with inadequate parenting practices and a lack of positive cognitive and non-cognitive stimulation (Heckman and Masterov, 2004). In other words, such disadvantages are powerful predictors of adult failure in social and economic measures.

Heckman therefore goes on to discuss the Perry Preschool Program (Schweinhart et al., 2005) which is a 2-year experimental intervention for disadvantaged African American children between the ages of 3 and 4. This program involved morning programs at school and afternoon visits by the teacher to the child's home.

The “right time” to invest in “second chance” policies was also discussed. In which the author highlights that if society waits too long to compensate, it is economically inefficient to invest in the skills of the less favored, especially because recovery programs in adolescence and young adulthood are much more expensive to produce the same level of acquisition of skills. skills. In other words, most of these problems are economically inefficient.

The author carried out an experimental evaluation in which the children were initially 3 or 4 years old, and were followed up until they were over 40 years old.

Furthermore, the report comments on a randomized study carried out by Carneiro and Heckman (2003), where the cost-benefit of classroom size on adult income for Tennessee was analyzed.

The group treated by Perry had IQ scores, at age 10, no higher than the control group. However, treatment children had higher achievement test scores than control children because they were more motivated to learn. In follow-ups until age 40, the treated group showed higher rates of high school completion, as well as higher wages, fewer rates of receiving social assistance, and fewer arrests when compared to individuals in the control group (Schweinhart et al. , 2005). Similar results are obtained for other early intervention programs (Karoly et al., 1998; Masse and Barnett, 2002).

By third grade, differences in test scores between socioeconomic groups are stable by age, suggesting, according to Heckman, that later schooling and variations in the quality of education have little effect on reducing or widening gaps that appear before students begin the school period (Cunha et al., 2006).

The results for classroom size in the Heckman and Carneiro (2003) study demonstrated some effect of reduced classroom size on test scores and adult performance. However, it is important to highlight that most of the effect was found in the first grades. Therefore, schools and school quality at current funding levels contribute little to the emergence of differences in test performance or development.

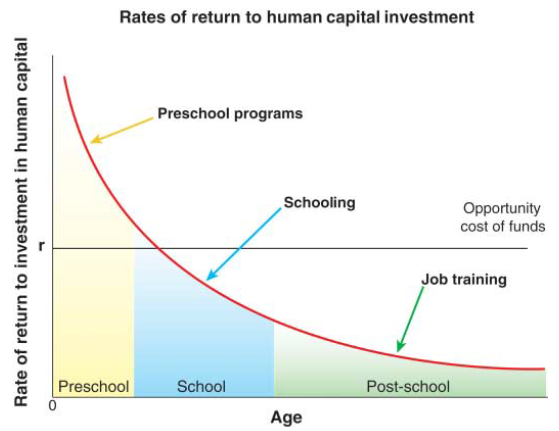

Figure 1 presents the rate of return, that is, the flow of dollars from a unit of investment at each age to a marginal investment in a disadvantaged child. This shows that the economic return on early interventions is high, whereas the return on interventions carried out later is lower. Therefore, Figure 1 highlights that at current funding levels, there is too much investment in most school and after-school programs, but too little investment in preschool programs for disadvantaged people.

From these findings, the author concludes that early interventions targeting disadvantaged children have much higher returns than later interventions.

Figure 1: Rates of Return on Investment in Human Capital in Disadvantaged Children

Source: Heckman (2006).

In his conclusion, the author emphasizes that investing in disadvantaged young children is a rare public policy initiative that promotes equity and social justice and, at the same time, promotes productivity in the economy and society as a whole. However, at current levels, society overinvests in remedial skills at later ages and underinvests in the early years. That is, the author emphasizes the need to change the period in which investments in corrective skills occur.

References

Carneiro, P.; Heckman, J. J. (2003). Inequality in America: What Role for Human Capital Policies?

Coleman, J. S. (1966). Equality of Educational Opportunity . US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Office of Education , Washington, DC.

Cunha, F.; Heckman, J.J.; Lochner, L.; Masterov, D.V.; Hanushek, EA; Welch, F. (2006). Handbook of the Economics of Education. Chap. Interpreting the Evidence on Life Cycle Skill Formation , 1, 697-812.

Delong, J.B.; Katz, L.; Goldin, C. (2003) in Agenda for the Nation , 17-60. Aaron, H.; Lindsay, J.; Nivola, P. Eds. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Ellwood, DT (2001) in The Roaring Nineties: Can Full Employment Be Sustained? 421 -489. Krueger, A.; Solow, R. Eds. Russell Sage Foundation, New York.

Heckman, J.J.; Masterov, D. V. (2004). The Productivity Argument for Investing in Young Children . Working Paper No. 5, Committee on Economic Development, Washington, DC.

Karoly, LA et al. (1998). Investing in Our Children: What We Know and Don't Know About the Costs and Benefits of Early Childhood Interventions . RAND, Santa Monica, CA.

Masse, LN; Barnett, W. S. (2002). A Benefit Cost Analysis of the Abecedarian Early Childhood Intervention. Rutgers University, National Institute for Early Education Research, New Brunswick, N.

Schweinhart, LJ et al. (2005). Lifetime Effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study Through Age 40 . High/Scope, Ypsilanti, MI.

Shonkoff, J.P.; Phillips, D. (2000). From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Child Development . National Academies Press , Washington, DC.

Statistics Canada (2002). International Adult Literacy Survey, 2002 : User's Guide, Statistics Canada, Special Surveys Division, National Literacy Secretariat, and Human Resources Development Canada. Ottawa, Ontario.