Responsible researcher: Eduarda Miller de Figueiredo

Article name: Reversal of Fortune: Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution

Authors: Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James A. Robinson

Intervention Location: World

Sample Size: -

Sector: Development

Variable of Main Interest: Per Capita Income

Type of Intervention: Urbanization

Methodology: OLS

Summary

Among the areas colonized by European powers during the last 500 years, those who were relatively rich in 1500 are now relatively poor. To analyze the reversal of relative income between the European formation colonies, data from 1,500 and data from the base year of the study were used. It was found that the reversal of relative rents is a result of the different profitability of alternative colonization strategies in different environments. In densely populated prosperous areas, Europeans introduced or maintained existing extractive institutions to force the local population to work more in mines and plantations, taking over existing tax systems.

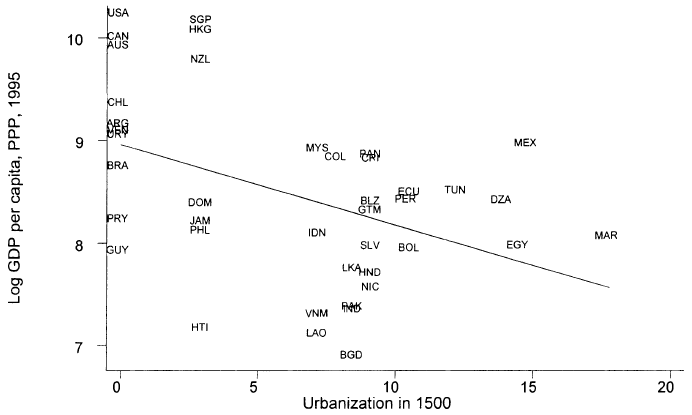

The article analyzed here deals with the reversal of relative income among European formation colonies. And, to this end, the authors present Figure 1, which shows a negative relationship between the percentage of the population living in cities with more than five thousand inhabitants in 1,500 and per capita income in the year of the study.

Figure 1 – Log of GDP Per Capita in 1995 against the Urbanization Rate in 1995

According to the authors, from Figure 1, an interesting pattern is observed as it provides an opportunity to distinguish between a number of competing theories of the determinants of long-term development. In which the “geography hypothesis”, one of the most popular theories, would explain most differences in economic prosperity by geographic, climatic or ecological differences between countries. Predicting that nations and areas that were relatively wealthy in 1500 should also be relatively prosperous today. However, the inversion of relative returns is evidence that does not corroborate the geography hypothesis.

For the authors, the “institution hypothesis” that relates differences in economic performance to the organization of society is the one that best explains the patterns they document. Where societies that provide incentives and opportunities for investment will be wealthier than those that fail to provide such incentives.

Given this, the authors hypothesize that a group of institutions that guarantee secure property rights to a broad cross-section of society, which the authors refer to as private property institutions, are essential to investment incentives and economic performance as well. -successful. And, in contrast, extractive institutions, which concentrate power in the hands of a small elite, are likely to discourage investment and development.

Civilizations in Mesoamerica, the Andes, India and Southeast Asia were richer than those located in North America, Australia, New Zealand or the southern cone of Latin America. However, Europe's intervention reversed this pattern. And this, according to the authors, is an important fact for understanding economic and political development, as well as for evaluating the various theories of long-term development.

Historical data and econometric evidence suggest that European colonialism caused an “institutional reversal,” that is, European colonialism led to the development of private property institutions in previously poor areas, while introducing extractive institutions or maintaining existing extractive institutions in previously prosperous places. . The main reason for the institutional reversal is that the relatively poor regions were sparsely populated, and this allowed Europeans to settle in large numbers and develop institutions encouraging investment.

Bairoch (1988) points out that during pre-industrial periods much of the agricultural surplus was likely to be spent on transportation, so both a relatively high agricultural surplus and a developed transportation system were necessary for large populations. The authors complement this argument by empirically investigating the relationship between urbanization and income.

For the 1,500 data, urbanization estimates from Bairoch (1988) were used, augmented by the work of Eggimann (1999). In which they ran a regression of the Bairoch estimates on the Eggimann estimates for all countries where they overlap in 1900.

The main measure of economic prosperity in 1500 is urbanization as Bairoch (1988) and de Vries (1976) argued that only areas with high agricultural productivity and a transportation network can support large urban populations. As a proxy to add for prosperity, the authors use population density.

The authors point out that the estimates of urbanization and population in 1,500 would probably have errors and, therefore, the negative coefficients found in the first results may be underestimated. Furthermore, a serious problem would be whether errors in urbanization and population density estimates were not random, but rather correlated with current income in some systematic way. To correct this possible “error”, the authors used a variety of different estimates for urbanization and population density.

When regressing the log of per capita income in 1995 on urbanization rates in 1,500 for the sample of former colonies, the authors find as a result the relationship that an urbanization rate of 10 percentage points lower in 1,500 is associated with approximately the twice the GDP per capita in current times. In which they emphasize that this result is not simply a reversion to the mean (countries richer than the average returning to the mean), but rather an inversion.

As an example of this last statement, the authors bring the comparison between Uruguay and Guatemala. The native population in Uruguay had no urbanization, while Guatemala showed an urbanization rate of 9.2%. The estimate for the relationship between income and urbanization implies that Guatemala, at the time, was approximately 42% richer than Uruguay. And, according to the estimates presented by the authors, Uruguay should have been 105% richer than Guatemala at the time of the study – which is the approximate difference in the per capita income of the two countries in the most updated data -.

The authors become concerned that the relationship is being driven mainly by the “Neo-Europes”: the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia. Countries that are colonization colonies built on land that was inhabited by relatively undeveloped civilizations. Therefore, when performing the regression, a weaker, but still negative, relationship is proven. Therefore, the results are very similar. In all cases, there is a negative relationship between urbanization in 1500 and per capita income in 2000.

By using a variety of different estimates for urbanization and population density, to correct a possible “error” described in the previous topic, the authors find that the results are robust to a variety of modifications in the urbanization data.

From the results found, the authors conclude that the reversal in relative incomes is inconsistent with the simple geography hypothesis. Instead, they find that the reversal of relative incomes over the last 500 years appears to reflect the effect of institutions (and the reversal caused by European colonialism) on current income.

The authors argued that the reversal of relative rents is a result of the different profitability of alternative colonization strategies in different environments. In densely populated prosperous areas, Europeans introduced or maintained existing extractive institutions to force the local population to work more in mines and plantations, taking over existing tax systems. Furthermore, Europeans settled in large numbers and created institutions of private property, providing secure property rights to a broad section of society, encouraging trade and industry.

Therefore, the authors conclude that the reversal in income is due to the emergence of the opportunity to industrialize during the 19th century. In which, while societies with extractive institutions, or those with highly hierarchical structures, could exploit agricultural technologies effectively, the dissemination of industrial technology required the participation of a broad part of society. Therefore, the age of industry created a considerable advantage for societies with privately owned institutions. Thus, the authors state that these societies took much better advantage of the opportunity to industrialize.

References

ACEMOGLU, Daron; JOHNSON, Simon; ROBINSON, James A. Reversal of fortune: Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution. The Quarterly journal of economics , vol. 117, no. 4, p. 1231-1294, 2002.