Responsible researcher: Eduarda Miller de Figueiredo

Article title: DETERMINANTS OF DISPARITIES IN COVID-19 JOB LOSSES

Article authors: Laura Montenovo, Xuan Jiang, Felipe Lozano Rojas, Ian M. Schmutte, Kosali I. Simon, Bruce A. Weinberg and Coady Wing

Sample size: 43,754 individuals

Location of intervention : United States

Sector : Job Market

Type of intervention : Effects of Covid-19 on unemployment

Variable of main interest : Unemployment

Assessment method : Others

Policy Problem

The pandemic sharply reduced social and economic activity, with large sectors of the economy ceasing normal operations while the government's social distancing order lasted. In May, in some American states, both the public and private sectors restarted the opening of economic activity.

However, in March 2020 there was a significant increase in initial unemployment insurance claims which, regardless of state policy, demonstrated a large drop in job offers (Kahn et al., 2020). Just like Coibion et al. (2020), who estimate that unemployment far exceeded unemployment insurance claims in early April.

Assessment Context

The literature demonstrates that existing patterns of social stratification shape socioeconomic outcomes during economic crises.

For example, the fact that the Great Recession reduced the life expectancy of older workers, especially in the case of white men, as Dudel and Myrskylä (2017) suggest. Or also like the assessments of the short and long-term effects of Hurricane Katrina by subgroups of evacuees, from the point of view of the job market, fertility, marriage, among others (Zissimopoulos and Karoly, 2010; Scheneider and Hastings, 2015; Grossman and Slusky, 2019).

Given the particularities of the economic crisis resulting from Covid-19, it is important to understand which population subgroups were most affected, why they were, and how these effects can lead to disparities in well-being in the long term.

Policy Details

To carry out the study, the authors used a sample of data from the Basic Monthly CPS from February to May 2020, which contains all workers aged 18 to 65. The database has complete information on gender, race, education, state, residence, recent unemployment status, occupation code, and the CPS weight of the sample.

The authors defined a worker as recently unemployed if the person was registered as unemployed in the month of the survey and had been in this status for a maximum of 5 weeks when in March, 10 weeks when in April and 14 weeks when in May. Those defined as “absent from work” are employees who were “temporarily absent from their regular employment due to illness, vacation, inclement weather, labor disputes, or personal reasons, whether or not they were paid for the time off” (US Census Bureau, 2019 ). There was massive growth in these types of workers during February and May 2020, deserving particular attention as some furloughed employees may have been recorded as short-term absent rather than unemployed. Thus, the authors analyze measures of recent unemployment and employed but absent separately.

Data from the 2019 Occupational Information Network (O*NET) Work Context was also used, which reports measurements for 968 occupations. This database contains several questions, such as how employees perform specific tasks, the need for face-to-face contact with customers and co-workers, and the possibility of work being performed remotely. Such measures were captured before the pandemic, so work practice innovations that were induced by the health crisis are not captured.

Methodology Details

To compare unemployment in three recessions, the authors make the following distinction:

Seeking to connect work subgroups and workers' characteristics, the authors ran regressions where the dependent variable indicates whether the individual is recently unemployed or temporarily absent from work. With a vector group of covariates, the authors also use state fixed effects, due to the specific epidemiological conditions of each state.

Results

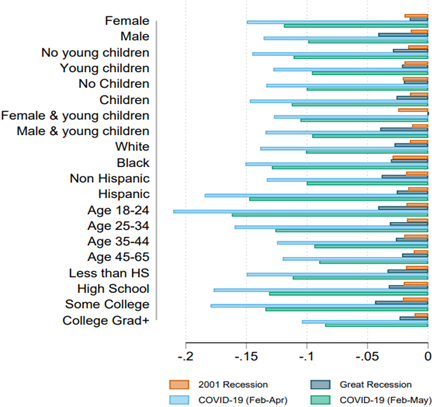

Job losses during the first months of the Covid-19 pandemic exceed the losses of the other two recessions, which span 9 months (2001 Recession) and 19 months (Great Recession), as can be seen in Graph 1. Furthermore, the Regressions suggest that recent unemployment rates vary with individual characteristics.

Almost no group is spared from unemployment during any of the three recessions. However, 18- to 24-year-olds and Hispanics have fared the worst during the Covid-19 pandemic. For the authors, this occurred because these groups work in sectors that are particularly affected by social distancing measures. Since Hispanics work more in jobs that cannot be done remotely and young people have jobs with more face-to-face interaction.

Unemployment was also polarized according to the level of education, that is, higher unemployment for those with up to high school and a bachelor's degree. More qualified workers are more likely to occupy essential positions, which justifies a lower unemployment rate.

Graph 1 - Job Change in the Three Recessions

In relation to family structure, married individuals have a lower unemployment rate than single people. In which women with young children have a higher rate of “employed but absent”, which is worrying and could indicate future unemployment. Single parents, the majority of whom are women (72%), suffered most from unemployment during the pandemic. However, the data shows that children's age is weakly related to employment change during the crisis. Therefore, efforts to support new child care options are extremely important in this pandemic scenario.

When analyzing the results, the authors realized that a substantial part of the difference in unemployment between subpopulations can be explained by differences in the pre-pandemic classification between occupations more and less sensitive to the Covid-19 shock.

Public Policy Lessons

In summary, the study suggests that the Covid-19 pandemic had different impacts on subpopulations and that these impacts were different from the impacts felt in recent recessions. Therefore, unemployment rates are very high among younger workers when compared to other subpopulations and also when compared to previous recessions.

Reference

MONTENOVO, Laura et al. Determinants of disparities in covid-19 job losses. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.