Responsible Researcher: Eduarda Miller Figueiredo

Original Title : Early Life Circumstance and Adult Mental Health

Authors: Achyuta Adhvaryu, James Fenske and Anant Nyshadham

Intervention Location: Ghana

Sample Size: 7,741 individuals

Sector: Healthcare

Variable of Main Interest: Mental Suffering

Type of Intervention: Early life events

Methodology: Measurement Analysis

Summary

This study aimed to study how early life circumstances affect psychological distress in adulthood. Early-life trauma can have outsized impacts on low-income populations, whose income smoothing and coping mechanisms are often limited. The results indicate that there is a negative impact of the price shock in the birth period on the logarithm of the K10 score. Furthermore, economic factors, such as monetary savings and self-employment, appear to contribute more to the total treatment effect than literacy, height, and BMI. In conclusion, low cocoa birth prices substantially increase the incidence of severe mental distress.

Mental health disorders are responsible for 13% of the global burden of disease. Even with a high percentage of mental illnesses, which lead to large economic losses, investment in prevention and treatment are still relatively low (Collins et al., 2011).

As a growing segment of the literature on fetal origins has documented, early-life trauma can have outsized impacts on low-income populations, whose income smoothing and coping mechanisms are often limited. Therefore, smallholder farming families in the developing world are exposed to frequent income fluctuations (Maccini and Yang, 2009).

This study aims to study how circumstances early in life affect psychological distress in adulthood. The choice to observe the beginning of life is due to the fact that recent literature has demonstrated that shocks and interventions in the early period of life have large and lasting impacts on health, as well as on the formation of human capital (Almond and Currie, 2011; Heckman , 2007).

The fetal origins hypothesis states that access to nutrition early in life has long-term effects on an individual's health and well-being. Changes in fetal programming can have diverse effects, such as physical health (Hoynes et al., 2012), educational performance (Bharadwaj et al., 2013) and the job market (Bhalotra and Venkataramani, 2012). Furthermore, medical evidence suggests that some components of mental health are encoded during pregnancy (Shonkoff et al., 2012).

Cocoa is Ghana's main agricultural export, and its price is a determining factor in family income in the regions where it is grown. Wide and persistent fluctuations in the price of cocoa directly affect the livelihoods of smallholder farmers, leaving families vulnerable to the harmful effects of shocks.

Households in the cocoa-producing region of Ghana experience changes in the real price of cocoa as income shocks, while households in non-cocoa producing regions are not affected by these fluctuations. Where children born into families in cocoa producing regions during periods of high cocoa prices will have more resources due to the family's higher income.

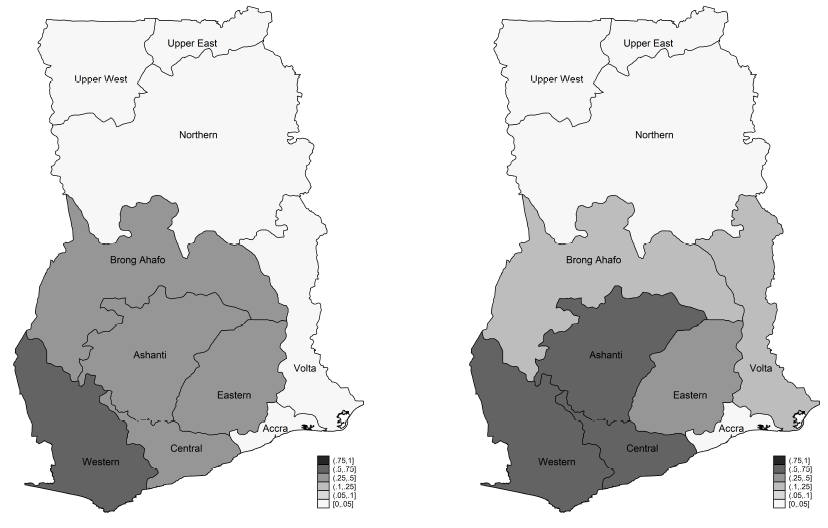

Figure 1 shows a map of Ghana with regions shaded according to the percentage of area dedicated to cocoa cultivation. The figure on the left shows the fraction of land planted with cocoa in each region, while the figure on the right shows the share of all land in the region that is suitable for growing cocoa.

Figure 1: Cocoa Production and Soils Suitable for Cocoa by Region

Source: Adhvaryu et al. (2018)

To carry out the research, the authors used a source of data on the real prices of cocoa at the producer, from Teal (2002), which reproduces the true real prices for the cocoa producer, which represents an opportunity for variable income over time, available for households in the cocoa-producing regions of Ghana, but not available in other regions of the country. Cocoa production data was taken from the EGC-ISSER Socioeconomic Panel Survey , for the period between November 2009 and April 2010 for all of Ghana.

The main measure of health is calculated using questions from the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10), as a measure of mental distress on the anxiety-depression spectrum. The questionnaire consists of 10 questions about negative emotional states experienced during the last 4 weeks.

Individuals who were born in Ghana and who are between 15 and 65 years old at the time of the research were analyzed, totaling a sample of 7,741 individuals.

The authors added an additional vector of controls ( x

) to the model, where the set of controls interacts the birth region fixed effects vector with a birth year variable, to allow for time trends specific to the birth region. Specific temporal trends for the region of birth were also added, as well as precipitation and temperature measurements.

The authors also carried out a measurement analysis applying inverse probability weighting (Heckman et al., 2013; Huber, 2014), which involves estimating the degree to which the impacts of shocks on mental distress vary according to the values of candidate factors for mediation.

The main estimates demonstrate that there is a negative impact of the price shock at birth on the logarithm of the respondent's K10 score in adulthood. The magnitudes of the effects on the logarithm of the K10 score are moderate, while the impacts on severe distress are large.

The real producer price has varied greatly over time and an increase of 1 standard deviation in the logarithmic price is equivalent to 0.55 logarithmic points. In other words, for an individual who was born in a cocoa-producing region, there is already a reduction in the log K10 score of approximately 1% of the average. For severe hardship, a price shock leads to a reduction of about 3 percentage points in severe hardship, which is almost half the average.

Individuals who received beneficial cocoa price shocks in their year of birth are less likely to report being depressed. Likewise, they are more likely to identify as relaxed. For the authors, these are the expected characteristics of individuals with a lower probability of mental suffering as a result of favorable conditions in early life events.

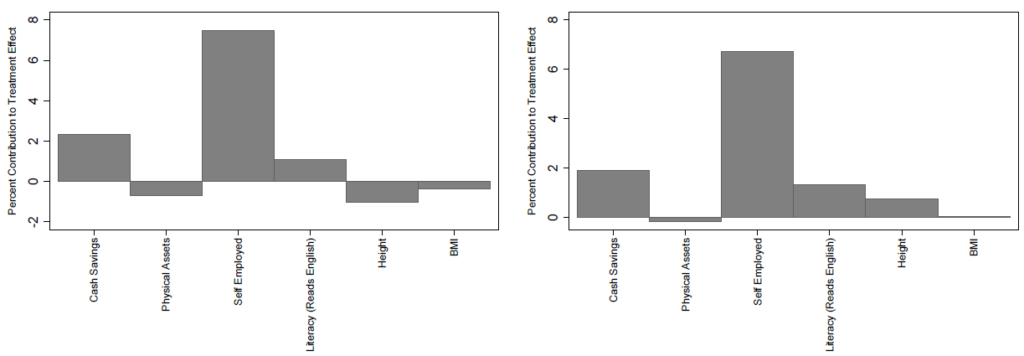

From the measurement analysis, the contribution of each factor to the effects on mental distress was calculated, as shown in Figure 2. The results indicate that economic factors, such as cash savings and self-employment, appear to contribute more for the total treatment effect than literacy, height and BMI. Furthermore, cash savings have a stronger effect on mental distress than the value of physical assets.

Figure 2: Measurement Analysis

Source: Adhvaryu et al (2018).

All six factors together account for about 10% of the total treatment effects on severe distress. The remaining 90% of treatment effects on mental health are the direct effect of the shock or mediated through other channels not measured for this sample.

Other results for adults were also estimated. The authors found positive impacts on labor force participation and substantial impacts on agricultural self-employment. In addition to positive impacts on the quality of housing (electricity and piped water) and accumulation of human capital (English, literacy and years of schooling).

Therefore, in cocoa-producing regions, low cocoa prices at birth substantially increase the incidence of severe mental distress, increasing the probability of severe mental distress by 3 percentage points, or almost 50% of the average incidence of severe mental distress, when compared to born in other regions of Ghana.

The authors' results suggest two mutually compatible interpretations of mental health impacts. First, mental health could be a mechanism that partially explains other economic problems from early-life shocks. Second, mental health is an end result that depends, in part, on these economic and health-related outcomes.

References

Almond, D. and Currie, J. (2011). Killing me softly: The fetal origins hypothesis. The Journal of Economic Perspectives , 25(3):153-172.

Bhalotra, S. and Venkataramani, A. (2012). Shadows of the captain of the men of death: Early life health interventions, human capital investments, and institutions. Unpublished manuscript, University of Bristol .

Bharadwaj, P., Loken, K., and Neilson, C. (2013). Early life health interventions and academic achievement. American Economic Review , 103(5):1862-1891.

Collins, PY, Patel, V., Joestl, SS, March, D., Insel, TR, Daar, AS, Bordin, IA, Costello, EJ, Durkin, M., Fairburn, C., et al. (2011). Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature , 475(7354):27-30.

Heckman, J. J. (2007). The economics, technology, and neuroscience of human capability formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 104(33):13250-13255.

Heckman, J., Pinto, R., and Savelyev, P. (2013). Understanding the mechanisms through which an inuential early childhood program boosted adult outcomes. The American Economic Review , 103(6):1-35.

Hoynes, H. W., Schanzenbach, D. W., and Almond, D. (2012). Long run impacts of childhood access to the safety net. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. w18535 .

Huber, M. (2014). Identifying causal mechanisms (primarily) based on inverse probability weighting. Journal of Applied Econometrics , 29(6):920-943.

Maccini, S. and Yang, D. (2009). Under the weather: Health, schooling, and economic consequences of early-life rainfall. American Economic Review , 99(3):1006-1026.

Shonkoff, J.P., Garner, A.S., Siegel, B.S., Dobbins, M.I., Earls, M.F., McGuinn, L., Pascoe, J., Wood, D.L., et al. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics , 129(1):e232-e246.

Teal, F. (2002). Export growth and trade policy in Ghana in the twentieth century. The World Economy , 25(9):1319-1337.